A perfectly sensible question I have been asked many times over the years – a source of fascination for tourists and necessary knowledge for locals. So I thought I’d give a simple explanation here. Enjoy.

Prior to European settlement, the landscape was in balance. The district was fully vegetated, mainly with woodlands. When it rained, the native plants drank the majority of the water that fell – their deep roots capturing most of it before it reached the groundwater table deep below. A small amount, around 5% of rain, ran off to the creeks and lakes. Local waterbodies such as Police Pools, Lake Ewlyamartup and the Carrolup River were fresh, and an important source of water for Aboriginal people and early settlers.

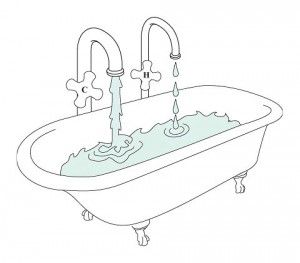

The groundwater fills up like a bathtub

Woodland + salinity = death

Saltbush planted on saline land, bringing life and productivity back.

Leave A Comment